A Passive House Designed for Aging in Place

Architect Gregory Beck Rubin crafts a home where his parents can grow old, while growing closer to nature

Though all good projects begin with a deep understanding of the client, it’s not every day that you have the luxury to design for clients you’ve known your entire life. Yet with this project along the Don Valley Ravine, Toronto’s first PHIUS+ certified home, architect Gregory Beck Rubin of Poiesis Architecture was able to do just that. After the 2013 ice storm left them without power for over a week, Beck Rubin’s parents began thinking about how they could make their home more resilient to climate change. With retirement around the corner, their ability to age in place was also top of mind. The original home was larger than they needed in the long term, so downsizing was always part of the plan—but the clients were deeply attached to the site, which backs onto the Don Valley Ravine, so enhancing the connection with the landscape became a top priority. Who better than their son to help them bridge these goals?

In designing their new abode, Beck Rubin had the advantage of seeing how his parents had lived in their previous home (and the ones prior). “I drew on a kind of archive of home experiences, and we used that to create reminders of what else was possible,” he explains. There was another important consideration: The clients had a collection of rugs from Iran and Afghanistan, and the space needed to be flexible enough to allow them to be swapped out at a moment’s notice. “It’s kind of a silly thing, but those are heirlooms in the family,” he continues. “There’s a joy in moving them around after several years, because they have such an impact on how each space feels and what you’ll do in it.”

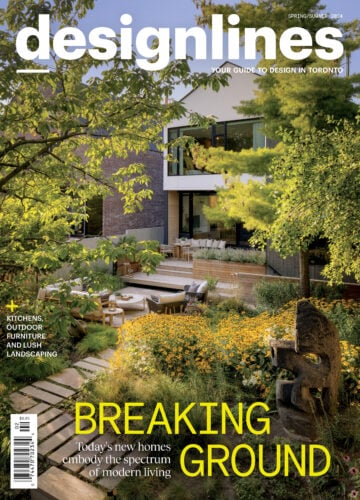

To that end, Beck Rubin sought to give his parents more open and interconnecting spaces, shifting away from the disparate rooms in their previous home. The south-facing street level hosts the primary bedroom, with a central mezzanine that acts as a transition to the more social areas on the lower, north-facing level, where living and dining spaces with wall-to-wall glazing look out to the Don Valley Ravine. From outside, the home now masquerades as a bungalow, like those that lined the street when they first purchased the property in the 90s.

The open concept not only allows for more flexibility but also a sense of intimacy. “It’s sort of settling because when they’re in the home, they look around and they can see the totality of it. There’s a sense of the wholeness,” he explains. “Our intuitive approach was that these spaces would lend themselves to more relaxed settings for aging in place.”

As for the finishes, Beck Rubin’s parents pretty much gave him carte blanche—and he ran with it. Unlike their former home, which was a traditional builder style with moldings and wood detailing, this one is a modern marvel. Throughout, local materials like pine, limestone and terracotta add texture and character, while reducing the project’s carbon impact. “We’re really lucky in Toronto to be so close to the production facilities of the materials we need for home building. While we can’t always build to carbon neutral, we certainly have opportunities to do better with our choices by just choosing locally sourced materials,” he says. A less is more approach also helps minimize material use: The concrete foundation walls, for example, were left exposed rather than covering them in drywall.

Thoughtful design choices will enable the home to grow with its residents. There are just two short steps to the front door from the yard, but there is a step-less entrance through the garage. Beck Rubin drew from the proportions of landscape steps to inform the interior stairs, making it easy and comfortable to move around, and there is an elevator should the owners ever need it. While the walls are prepped to install grab bars and there is additional space for live-in help, accessibility here is just about good design. Automated lighting systems and window coverings and digital appliances make it easy not just to age in place, but to live in place.

Most important to this idea of aging in place was to design a home that is climate resilient. Designing to Passive House standards was a no-brainer for Beck Rubin (who had ample experience with sustainable design in his previous work at Perkins&Will), given the framework’s clear focus on comfort and energy usage. Designing an airtight and super insulated envelope was critical to help the home run more efficiently using less energy. The results speak for themselves: The clients didn’t have a heating bill for the first 11 months they lived there. “In a way, aging in place was about security. Passive design was about giving them something that wouldn’t be a burden to manage into the future,” he says.

The Passive House certifications required extensive energy modeling and airtight testing. “Never in my life did I think that we could design a building looking north that would have so much openness because, from everything that I’d learned up until then, that was just going to be a leaking wall. But the energy modeling told us another story,” he recalls. They achieved Passive House standards by prioritizing ravine views while limiting windows where they wouldn’t add to the experience (for instance, on the east and west facades). In this way, the energy modeling helped guide the design process, allowing the designer to make more intentional decisions. “We often don’t think that being able to make a custom home has constraints, but it does,” he adds.

The home is nestled into the landscape, designed in collaboration with an urban forestry consultancy specializing in ravine stewardship and ecological restoration. The new design sees hard materials replaced by native plants. Looking out from the house towards the Don Valley Ravine, for a moment, you might forget you’re still in Toronto. In other words, the home becomes an escape from city life. “That was an ask from them,” says Beck Rubin. “My parents don’t have a cottage or a second home to go to. I wanted to give them a sanctuary or retreat, maybe more as a son than as an architect.”