Mid-Century Modern Designers Maps a Global Design History

In his sweeping new book, Dominic Bradbury gives 300 global designers their due

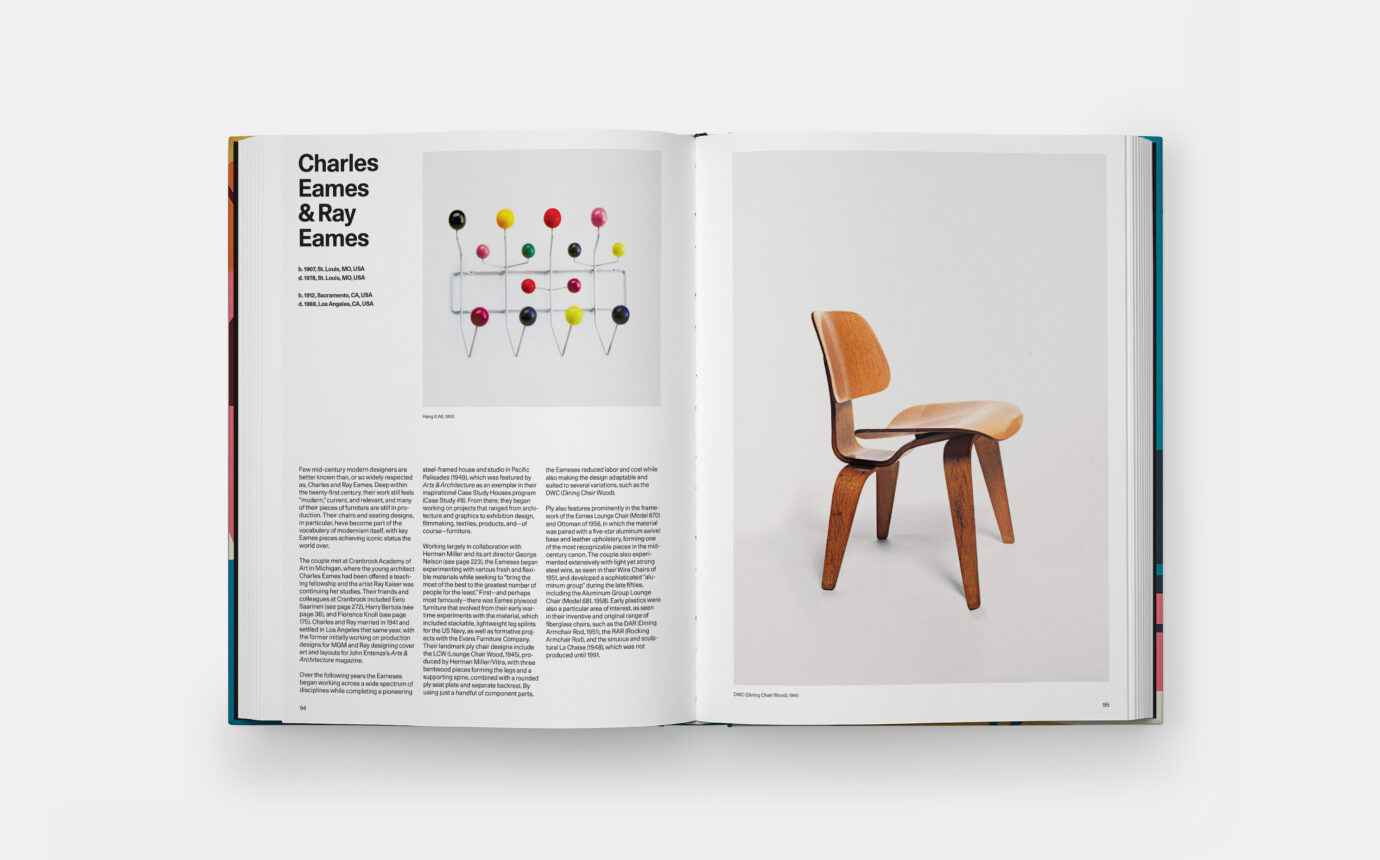

In Mid-Century Modern Designers, design historian Dominic Bradbury delivers what is arguably the most comprehensive survey of postwar design talent to date. With over 300 international profiles and 350 images packed into 352 elegantly designed pages, the book doesn’t just chronicle an era—it reanimates it.

Bradbury’s central thesis is clear: mid-century modernism wasn’t merely a style, but a cultural shift that brought democratic design to the global stage. Anchored by postwar optimism and industrial ingenuity, the movement embraced craft, mass production, sculptural aesthetics, and functional innovation. From the ever-iconic Eameses to lesser-known talents like Susi Aczel and Yoshio Akioka, each entry celebrates a practitioner who helped shape the look—and feel—of modern life.

Celebrating International Contributions

Organized alphabetically, the book functions as both reference and visual inspiration. It features marquee names like Alvar Aalto, Florence Knoll, and Verner Panton, but its true strength lies in how it broadens the canon. Figures from Brazil, Japan, Mexico, Australia, and Eastern Europe are given equal weight, reinforcing the book’s assertion that mid-century modernism was a truly global movement—not a Euro-American export. Notably absent, however, are Canadian designers. While Bradbury casts an admirably wide net, Canada’s contributions to mid-century design are overlooked. It’s a curious omission, especially given the country’s own postwar modernist legacy, and one that readers north of the border may find disappointing.

Shifting Aesthetics and Ideologies

Bradbury excels in contextualizing the era’s social, technological, and material evolutions. From the rise of studio craft to the mass adoption of plastics, the book captures the restless experimentation that defined the period. He traces how designers like Panton, Saarinen, and Poul Kjærholm embraced new materials not for novelty’s sake, but to solve real-world problems—streamlining production, enhancing ergonomics, and pushing boundaries of form.

Equally compelling is Bradbury’s discussion of cross-disciplinarity. Architects designed lamps, sculptors crafted chairs, and designers like Gio Ponti juggled buildings, furnishings, and magazines with ease. Today’s era of blurred creative boundaries owes much to this multidisciplinary ethos, and Bradbury deftly illustrates that lineage.

Readers will appreciate how the book bridges scholarship and delight. It’s scholarly without being intimidating, visually rich without resorting to coffee-table cliché. In many ways, it’s a companion to Phaidon’s Atlas of Mid-Century Modern Houses, but with a sharper focus on the makers themselves—those who merged art, craft, and industrial design into a new modern vernacular.

For collectors, curators, interior designers and devotees of the era, Mid-Century Modern Designers is a welcomed addition to your bookshelf. It reminds us not just why we love this era’s furniture and lighting, but how and why it came to define contemporary design in the first place.